The Limits of Retrieval-First Architectures

Late-stage GTM work rarely fails because the information doesn't exist somewhere. It fails because that information is trapped in places that aren't trivially accessible - in people's heads, buried in Slack threads, scattered across tools nobody checks - and when it is surfaced, teams apply the wrong version of it at the wrong moment.

A sales leader reviewing a forecast wants to know whether a product issue threatens close rates. A solutions engineer preparing a security review needs confidence that every claim reflects current approvals. A CRO evaluating pipeline risk needs insight that actually maps to their business, not a wall of raw data pulled from five different tools.

Most AI systems built for go-to-market teams follow the same architectural pattern: data is exposed through MCPs or APIs, queried on demand, and returned based on semantic similarity. From a systems perspective, this approach is clean, scalable, and familiar. It aligns well with modern enterprise search and the growing ecosystem of AI workplace tooling.

It also has a hard ceiling.

Retrieval-first architectures work when questions are narrow and the underlying data is already well structured. They break down when the task requires understanding how information relates across systems, evolves over time, or should be applied within a specific business context. GTM work is almost entirely composed of those harder questions.

The core limitation isn't the quality of retrieval. It's the absence of representation.

We've written before about how chunking your GTM data isn't the same as understanding it. This post goes deeper into why that distinction matters architecturally, and what it means for how AI systems should be built to support revenue teams in practice.

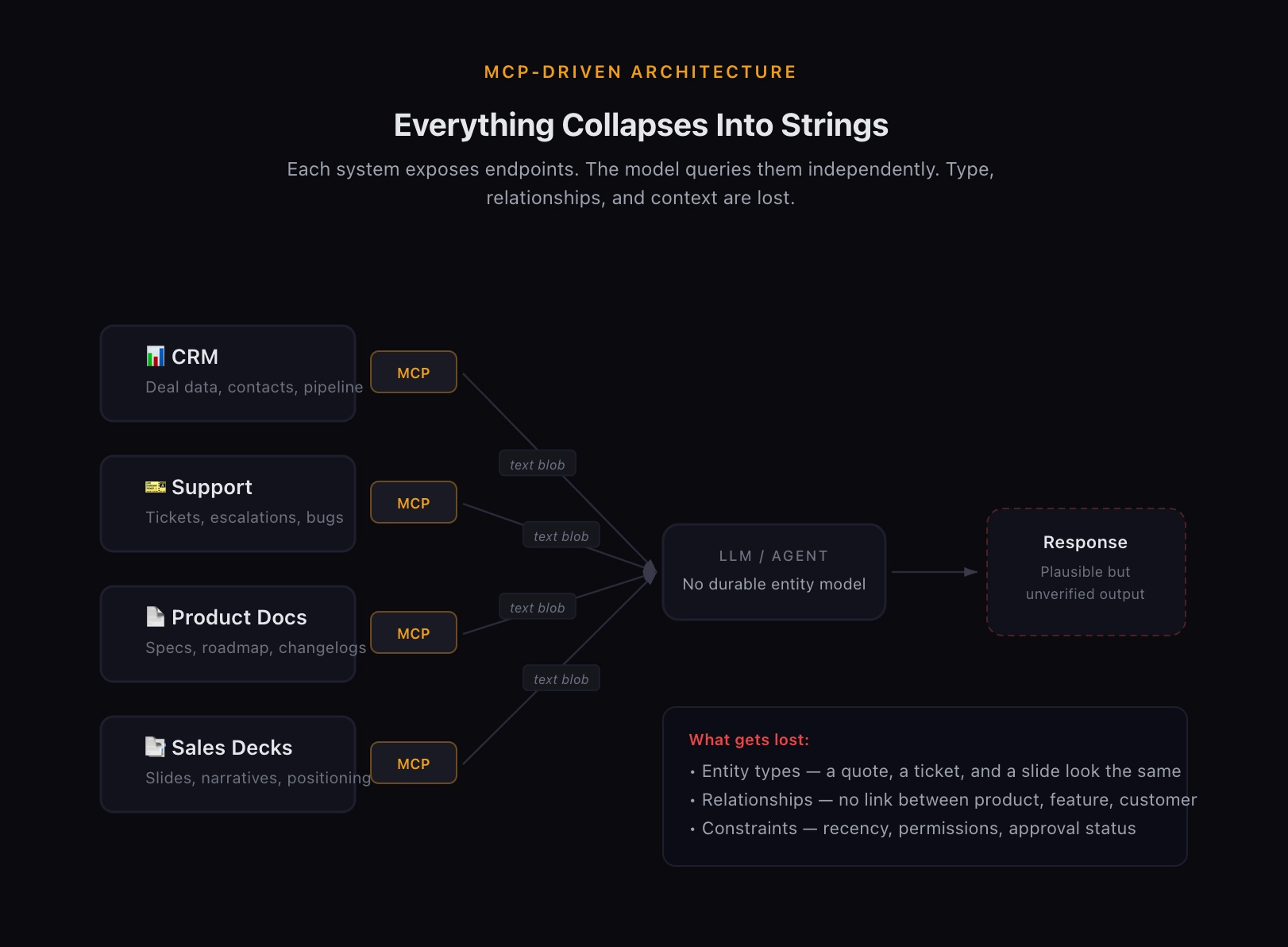

How MCP-Driven GTM Systems Actually Operate

In an MCP-driven architecture, each system exposes a set of endpoints. A model or agent issues queries against those endpoints, retrieves results, and uses the returned text as input for reasoning or response generation. Each call is evaluated independently. The model has no durable understanding of the entities behind the data. It only has the text that comes back.

From the model's perspective, everything collapses into strings.

A product roadmap update, a support ticket, a customer quote, and a sales slide are all reduced to generic, unrelated blobs. Any meaning about how they relate to one another, or why one should outweigh another must be inferred dynamically at query time, if it's inferred at all.

This creates several structural constraints that are worth naming explicitly:

First, information is queried in isolation, even when the underlying decision spans multiple systems. A rep preparing for a renewal call might need context from the CRM, recent support tickets, product release notes, and the original sales deck, but the system treats each of those sources as independent text, with no awareness that they describe the same customer journey.

Second, relationships between entities like products, features, customers, and permissions rarely survive the retrieval process. In theory, these relationships exist somewhere in your data. In practice, retrieval-first systems almost never reconstruct them. The connection between a customer quote, the product version it references, and the approval status of that quote for external use? That chain of meaning simply doesn't get built at query time. It's too contextual, too multi-layered, and too dependent on business logic that lives outside any single document.

Third, conflicts and recency fall entirely on the user to resolve. When a system returns two slides with slightly different positioning, or a quote from a customer who churned six months ago alongside one from an active champion, the system doesn't know the difference, unless the LLM happens to figure it out on the fly, which is possible but far from reliable. In practice, the human still does the reasoning. The AI does the fetching.

MCPs make it possible to access more data with less integration overhead. That's genuinely useful. But they do not provide a shared semantic layer that allows the system to reason across that data. Access and understanding are fundamentally different capabilities, and conflating them is one of the core ways AI has been oversold to revenue teams.

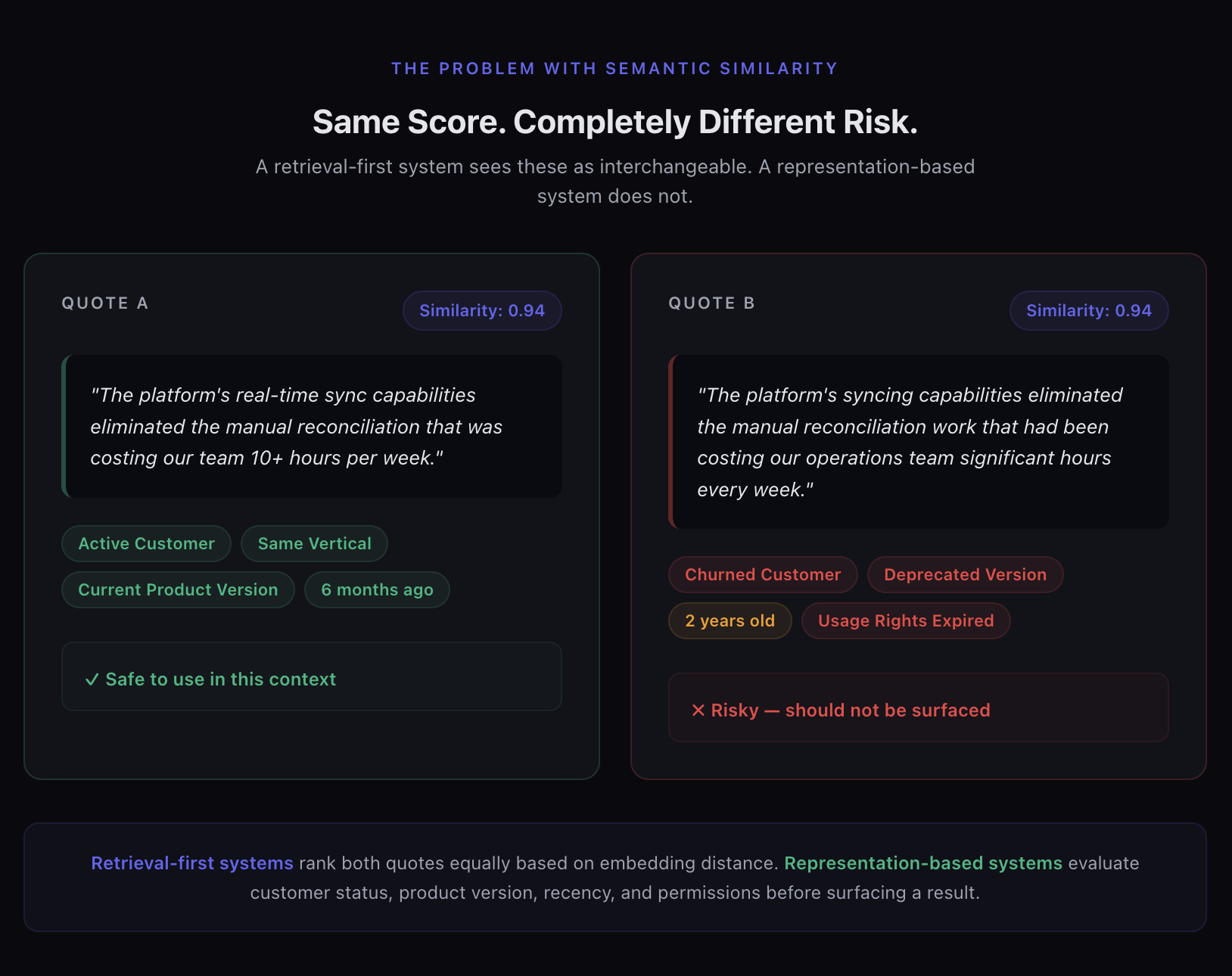

Why GTM Questions Require More Than Semantic Similarity

Consider a common late-stage deal scenario. A rep asks an AI system for a customer quote supporting a specific feature. The system retrieves two quotes that are nearly identical in wording and embedding similarity. One came from a customer in the same vertical six months ago. The other came from a churned customer two years ago, referencing an older version of the product.

To a retrieval-first system, these quotes look interchangeable. To a GTM team, they are not even close.

Most GTM questions are not about whether information exists. They're about whether information applies.

A sales rep isn't asking if a quote mentions a feature. They're asking whether that quote is appropriate for this customer, in this industry, at this stage of the deal, under current product scope and permissions. A solutions engineer isn't looking for a slide about architecture. They're looking for the right slide that reflects current positioning, avoids outdated claims, and can actually be shared externally. A revenue leader asking for competitive positioning doesn't just want a battlecard to exist in the system; they need to know the battlecard reflects the latest product moves and win/loss data, not something that was accurate two quarters ago.

Semantic similarity alone can't answer those questions. Two pieces of content may be close in embedding space while being materially different in relevance once customer segment, product version, or recency is applied.

This is where retrieval-first systems fail quietly. They return something plausible. They return it confidently. But because they are guessing without the context needed to evaluate what they've found, they produce what you might call confident failures: answers that look right, feel authoritative, and turn out to be wrong in ways that only surface when a customer pushes back or a deal goes sideways. As we explored in our post on the internal knowledge problem, the cost of these failures isn't just wasted time. It's eroded trust, both with customers and within your own team.

Representation as a First-Class Architectural Choice

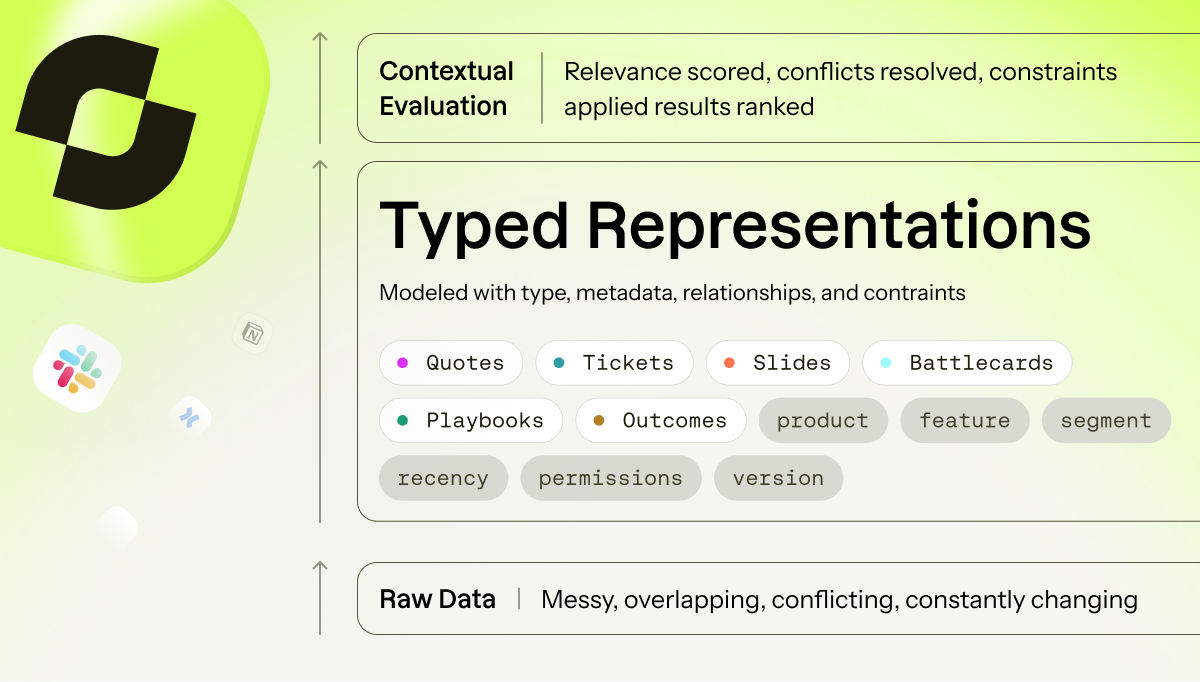

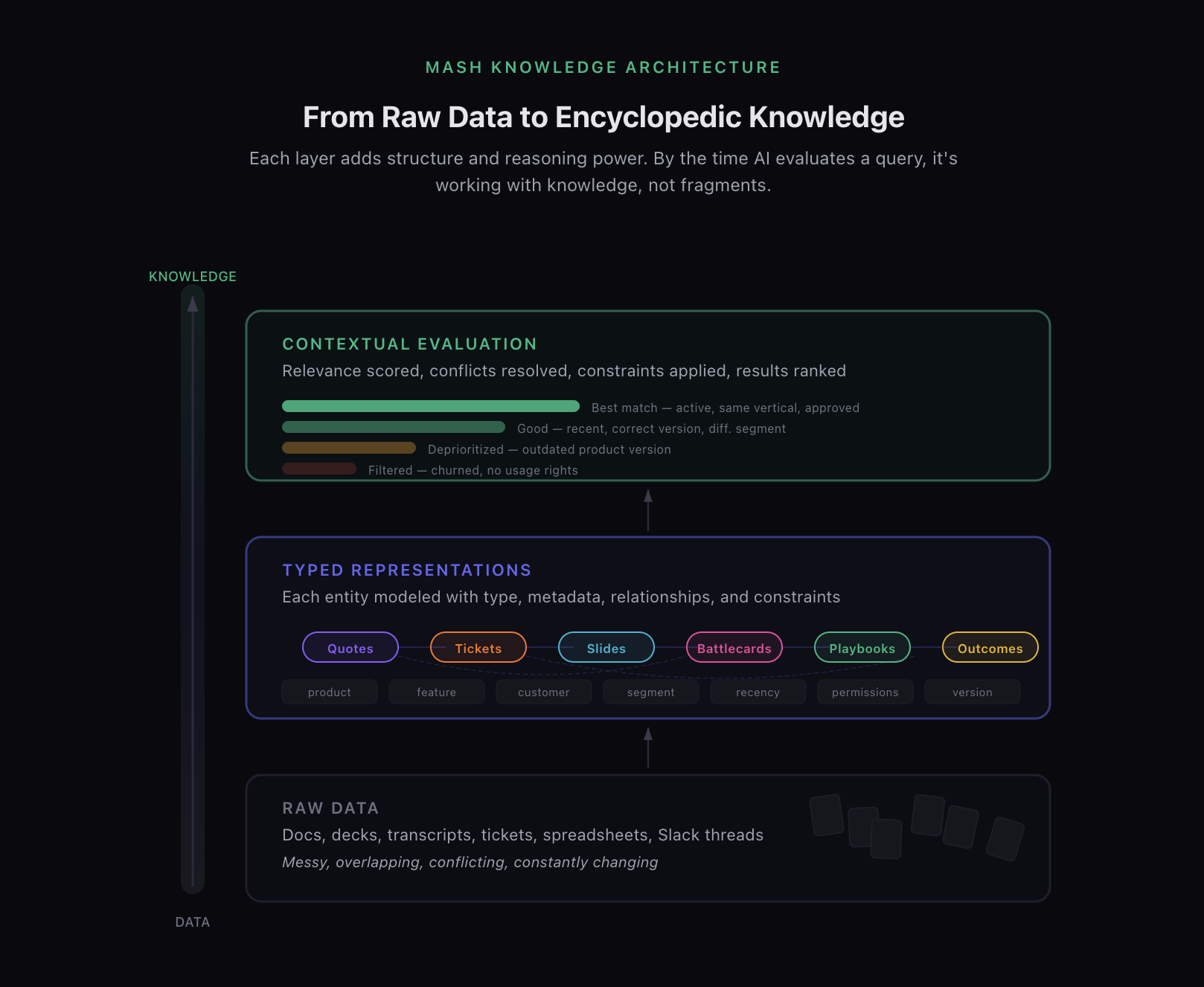

Mash approaches this problem differently by modeling explicit representations of the entities GTM teams care about.

Products, features, slides, battlecards, objection handling frameworks, customer quotes, proof points, support tickets, outcomes, and permissions are not inferred opportunistically at query time. They are encoded as first-class objects within the knowledge system. Relationships between these objects, such as which features belong to which products, which quotes are tied to which customers, which battlecards map to which competitors, and which assets are approved for which audiences, are defined directly in the model.

This shifts the role of AI from interpretation to evaluation. And critically, it allows the system to leverage what large language models are actually exceptional at: handling encyclopedic amounts of information. The difference is that with representation, what the model operates on is encyclopedic knowledge, not random data. The structure is already in place. The relationships are already mapped. The model's job isn't to guess what a piece of content means or how it connects to everything else. Its job is to evaluate, prioritize, and apply what the system already understands.

Instead of asking the model to infer structure from text at query time (and hoping it gets it right), Mash provides the structure upfront. The system knows what a quote is. It knows what a ticket represents. It knows how a slide fits into a broader narrative and when that narrative was last updated. It knows which objection handling approach maps to which persona and deal stage. That knowledge doesn't get reconstructed on every query. It persists.

How Representation Changes Retrieval

This architectural choice fundamentally changes how information is stored, indexed, and surfaced to users.

Rather than relying on a single vector store with generic chunking, Mash maintains multiple representations optimized for different GTM workflows. Quotes are extracted as quotes, linked to customers, products, features, and outcomes, and tagged with constraints like usage rights and freshness. Support tickets are represented in relation to affected features and products. Slides and documents are modeled as evolving narratives, not static text artifacts. Sales playbooks are structured so that discovery questions, objection responses, and competitive positioning reflect specific personas, verticals, and deal stages rather than living as flat documents that a model has to interpret from scratch.

Vector search still plays a role in this architecture, but it is not the system's source of truth. It becomes one signal among many.

When a query enters the system, Mash does not simply retrieve the closest chunks by embedding distance. It evaluates relevance across representations, applies constraints, resolves conflicts, and weights information based on context. Two quotes that appear similar semantically may be ranked very differently once deal stage, customer segment, or recency is taken into account. A battlecard that matches a competitor name might be deprioritized because it hasn't been updated since a major product shift.

This is how the system surfaces the most important insights rather than the most similar ones.

Visualizing the Difference

The contrast becomes clearer when you think about the architectures side by side.

In a typical MCP-based system, data is pulled from multiple tools at query time, stitched together loosely, and presented without a shared understanding of how those systems relate. Each source remains semantically isolated. The user receives fragments and is expected to assemble meaning from them.

In Mash's knowledge engine, information from those same sources is ingested into a shared domain model. Meaning is preserved through representation, allowing the system to reason about relationships, conflicts, and applicability before anything is surfaced to the user. The evaluation happens upstream, not improvised dynamically by the LLM at runtime, and not in the rep's head during a live call.

This distinction matters more as GTM stacks grow more complex. Adding more tools to a retrieval-first system doesn't create clarity. It creates more fragments. More tools only generate better outcomes when there's a model that unifies them, and that model has to understand your business, not just your file system.

Why This Matters for Revenue Teams

For revenue teams, the difference between retrieval and representation shows up in the workflows that actually drive deals forward.

The questions they ask are rarely academic. They're contextual, time-sensitive, and tied directly to risk or opportunity. Is this claim still valid? Can this proof be shared externally? Does this content reflect our current positioning? What's the best deal strategy and set of discovery questions for this persona and this specific situation? That last question alone requires the system to deeply understand your sales playbook, your product's competitive landscape, the customer's industry, and the stage of the deal. No amount of semantic search against a chunked document library is going to produce a reliable answer to that.

MCPs and APIs make data accessible. Representation makes data intelligible.

That architectural decision is what allows a system to move from search to insight, supporting not just faster answers, but better decisions. And in GTM work, better decisions compound. A rep who trusts the system enough to use it in a live conversation moves faster than one who has to stop and verify. An SE who can pull the right technical proof point without a 30-minute hunt spends that time on higher-value work. A revenue leader who gets a pipeline view informed by real product and customer context makes better calls about where to invest their team's energy.

From Access to Understanding

As AI becomes more deeply embedded in revenue workflows, the limiting factor is no longer connectivity. It's comprehension.

Retrieval-first systems optimize for access and speed. Representation-based systems optimize for correctness, applicability, and trust. For GTM teams operating in high-stakes environments where a wrong answer costs more than no answer at all, that distinction matters more than raw recall.

Mash is built on the belief that enterprise search is table stakes. The real advantage comes from modeling how GTM knowledge actually works: across products, customers, permissions, and time. Not just indexing what your team has created, but understanding what it means, when it applies, and how it connects to everything else.

That shift, from retrieval to representation, is what turns knowledge into leverage. And it's what separates AI that your team actually trusts from AI that becomes just another tab they learn to ignore.